SpaceChem is a puzzle computer game made by Zachtronics intended to teach computational thinking for players of unspecified ages. While the context of the puzzles revolves around chemistry, the core challenge of the puzzles revolves more around how to synchronize discrete operations in elaborate machines to work together towards specified goals efficiently in open-ended environments. That is to say, the chemistry serves as a backdrop, rather than the core learning objectives.

Learning Objectives

Chemistry Knowledge

SpaceChem does not require prior knowledge of chemistry, as it teaches players the necessary chemistry concepts as a part of the tutorial. This domain knowledge (taught in the tutorials) consists primarily of the following concepts:

- Atoms are the basic building block of chemicals. Atoms are divided into different elements, which behave differently.

- Atoms can bond together to form molecules; different combinations of atoms form different molecules, while the specific orientation of where the atoms are does not matter (this is an oversimplification to make the puzzle solving more open-ended and less domain-focused)

- New bonds can be formed between atoms to make different molecules, and old bonds can likewise be broken to form new molecules.

- Each element has a maximum number of bonds that its atoms can make. This maximum number of bonds is specific to the element.

Computational Thinking

More important than the above chemistry knowledge, the game requires a degree of proficiency in computational thinking, and most of all, grit. It is difficult to pin down exactly which skills are prerequisite vs learned in-game because in principle, players can learn the computational skills the game demands through trial and error while playing. That said, the game is generally accepted as quite difficult by its players and will presumably be inaccessible to players with a low frustration tolerance. One can compensate for lower computational thinking skills with patience and grit – if players start with a lower skill level as well as low tolerance for frustration, then they are likely to get little out of the experience. Below are my impressions of the skills that can be learned/improved by playing the game.

- Players will use directional commands and rotation to ensure that the relevant pieces are brought to the correct places in correct orientations on the board in the right order.

- Players will use synchronization commands to control the timing of execution across parallel processes to insure that the correct commands are executed in the correct sequence.

- Players will identify opportunities to incorporate previously implemented constructs as component parts of a solution to a more complex problem and apply these components effectively in context.

- Players will refactor their solutions to be more efficient by using fewer commands and/or taking fewer cycles (less time) to run to completion.

- Players will identify which aspects of their solution are failing and why in order to revise their solution based on the observed results.

- Disposition: Players will persist in the face of failure and learn from their mistakes and partial-solutions as described in skill 5.

The disposition (Goal 6) is not so much learned in the game as it is a prerequisite. If players do not approach their failures in this way, they are likely to be turned off and quit the game. The only negative review of SpaceChem on the front of its steam page says,

“If you’re someone who likes playing video games for fun rather than reward, you’ll probably not find much to enjoy with SpaceChem.”

This is apt, as players really must be self-motivated to tackle the game’s challenges in order to get much from the experience. That said, for those with the grit to stick through the game’s challenges, the difficult puzzles will present further opportunity for players to practice their persistence.

Transfer

The dispositional goal is the seems the most likely to transfer to other problem solving contexts – grit will always be valuable to facing challenges. The domain knowledge imparted (regarding atoms, molecules, etc.) is unlikely to be particularly useful, as it is rudimentary compared to the difficulty of the puzzles. Most players able to tackle the games intense challenges are likely to already have most of the real chemistry knowledge the game imparts, and those that don’t are unlikely to have mastered the complex skills used in high school chemistry (like balancing chemical equations, making stoichiometry calculations, etc) though they may remember a few chemical formulas.

Likewise, the computational thinking goals are not obviously transferrable into acutal programming or mathematical contexts, as the specifics of the moves used to address the game’s challenges are unique to the game (like using a ‘sync’ command to make one process wait for another before proceeding – while there are analogies that can be drawn from technique to coping with asynchronicity in programming, the actual techniques used in-game are not obviously transferrable).

With that in mind, players who are not experienced programmers, may cultivate an awareness of certain kinds of problems that computational solutions may encounter: e.g. it could be the case that one function takes longer to complete than another, and that this can cause problems if not well handled. Likewise, the techniques used to ‘refactor’ solutions to make them more efficient may not transfer to other computational contexts, but the general value of elegance (in terms of a solution’s compactness and the speed with which it runs) are valuable considerations outside of the game. So it seems most likely that the transferable benefits of the game from a learning standpoint are primarily in an awareness of certain categories of considerations as outlined above, rather than developing the tools to solve computational problems directly. So players can be expected to learn that they should check that a computational solution is executing commands in the right order, avoiding race conditions, making use of abstraction to repeat previously figured out sub-calculations, and running efficiently, but they cannot reasonably be expected to be able to check these things in an out-of-game context, because the tools and techniques used to do so will be significantly different than their in-game experience.

Mechanics

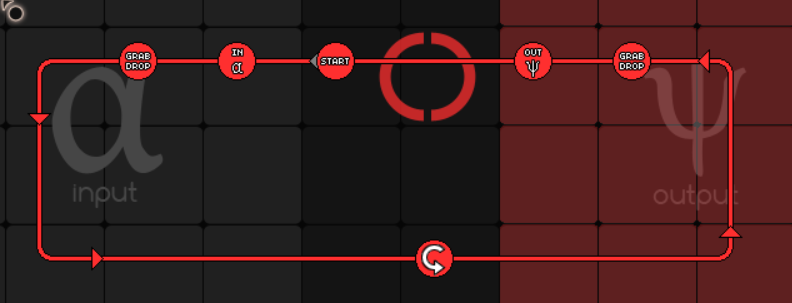

Gameplay centers around iteratively developing circuit-like machines that run parallel processes on a grid. Your goal is to convert several elements or compounds into other chemical products by stringing together the right series of commands within spatial constraints. Each reactor you create has its own grid which can contain two parallel circuits, one red, and one blue. Each circuit has its own set of commands and its own ‘waldo’, a circle that navigates the circuit and executes each command when it crosses the block representing the command.

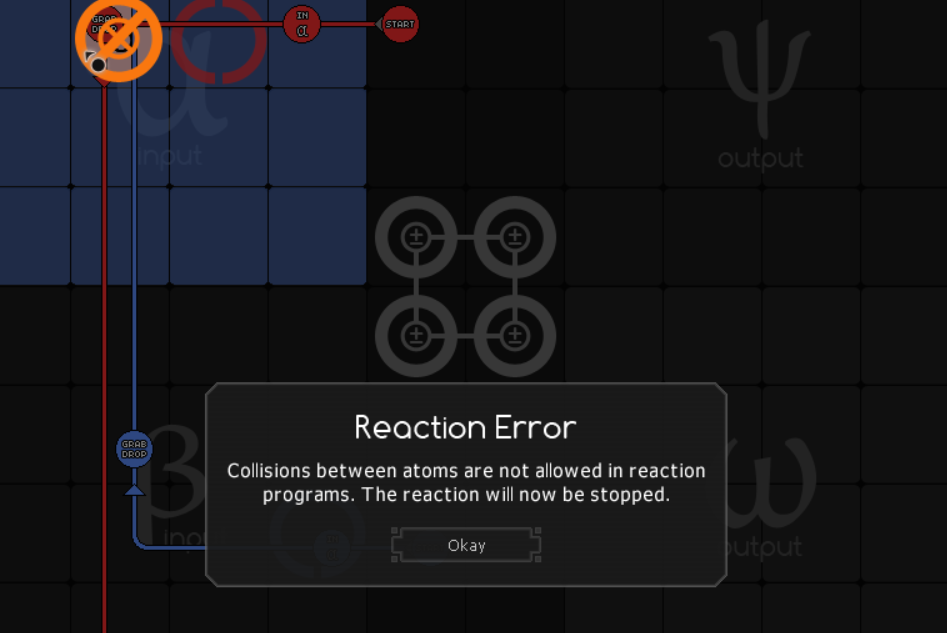

Commands include dropping new elements onto the board, picking them up or dropping them, turning them around, bonding them together, and outputting desired molecules when they are formed. Each reactor includes two circuits running at the same time. These circuits must be used together and synced up at the right points to ensure they work together to build the desired molecules and put them in the right places at the right times. If two atoms touch each other (hit the same grid cell at the same time) the program crashes and the player must adjust their circuits to fix the problem.

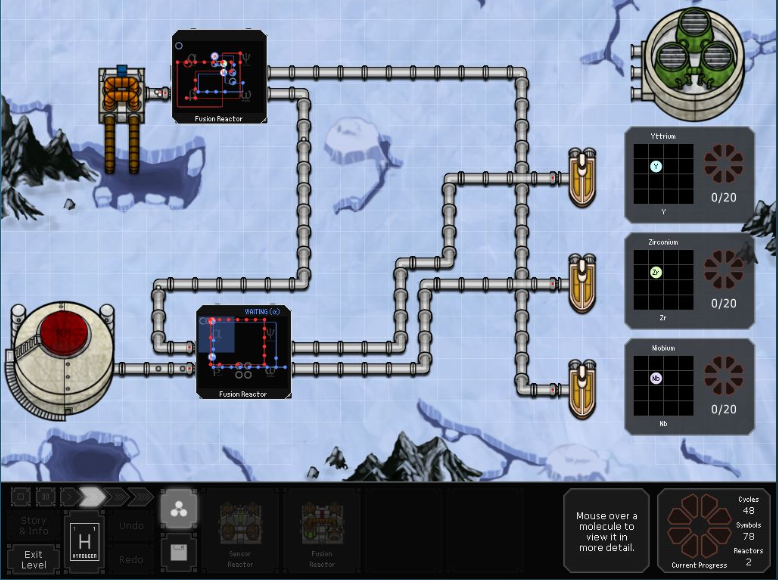

The game is further complicated by eventually introducing levels that require multiple reactors in order to produced the desired results. This emphasizes the process of building very complex systems by individually building functioning systems and integrating them together into a larger whole.

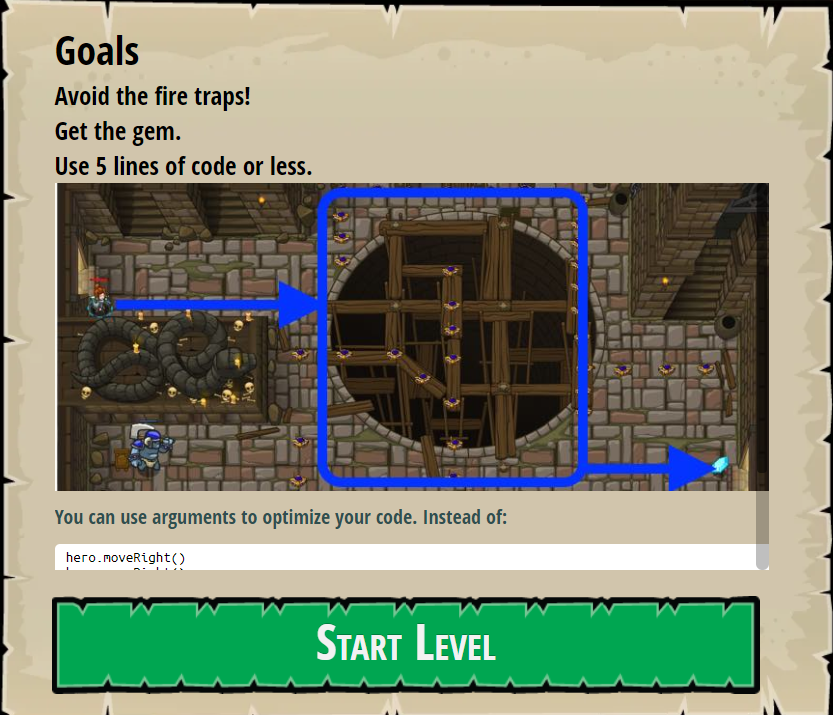

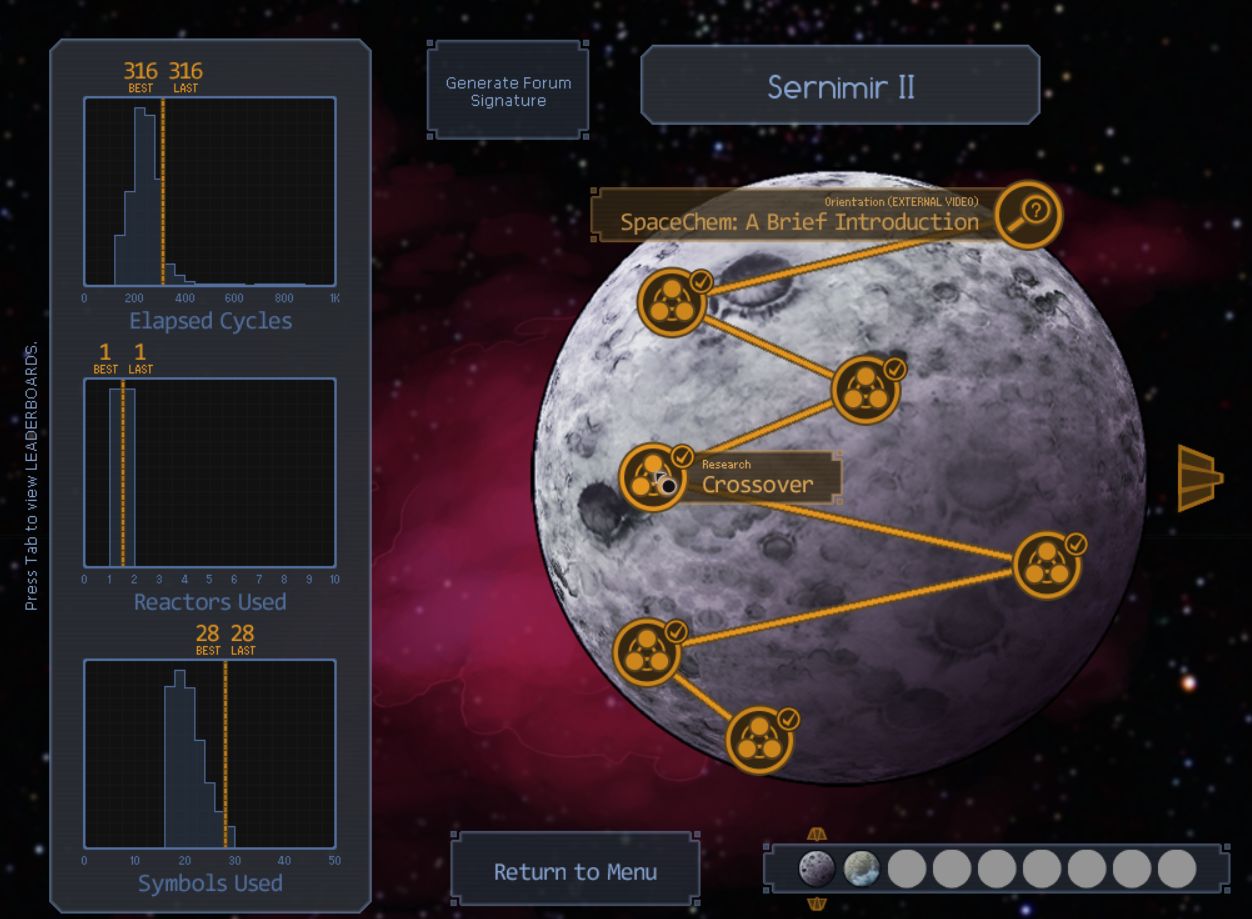

Each level selection screen visualizes the player’s solution in terms of the number of cycles elapsed (runtime required for the solution to beat the level), the number of reactors used, and the total number of symbols used (number of commands). Further, the game includes achievements that encourage players to be efficient in their solutions to various levels.

Together, these incentives encourage players to go beyond solving a problem any way they can and to instead seek a good solution for each level.

Dynamics

It is difficult to plan out a full solution to a level in advance of running your program. Small differences in the timing between both circuits, as well as the precise position and orientation of the input molecules makes it very difficult to know whether you’ve totally got it until your program works (or doesn’t). Even when you know that your solution is incomplete, it’s difficult to anticipate what the most immediate problem with your current implementation will be before you run it and see where it crashes. This encourages the player to be very iterative in their approach. There is no penalty for trying and failing. I found myself very often implementing a small part of what I thought was needed and checking whether things wound up where I expected by running it (and having it crash somewhere), then picking up from there by identifying what needs to happen next (or what is happening that shouldn’t) and fixing one small piece at a time before running and re-evaluating, over and over until I had a working solution.

Each partial solution will yield a different result that must be analyzed in order to improve and beat the level. My most common mistakes were to fail to fail to grab an atom either because I misjudged where it would be placed, to mis-time my outputs so that the beginning of the next loop crashed an atom into the end of the previous loop, and to simply forget to drop an atom in the output area. Below is my journey through one of the earlier levels:

That said, it’s certainly possible to fully implement a functioning solution on the first try and only run the level once. This would be a feat of meticulous planning well beyond my own abilities, though. I assume that most players take a similarly iterative approach to my own.

The incentives for time and fewest-commands efficiency (scores and achievements) also encourage players to go back and try again once they’ve completed a level. In that sense, the outer loop between levels can be as iterative as as the inner loop of solving one level.

Aesthetics

I would describe the overall feeling of playing the game as iterative solution-crafting. Each run presents the opportunity to address a key problem with the previous implementation, while likely invoking new problems that ultimately bring you one step closer to a viable solution. The open-ended nature of the puzzles evokes feelings of discovery and self-expression. The more complex the challenge, the more pride one finds in their individual solution. Part of the appeal is certainly the challenge; most of the reviews on steam mention intelligence in one way or another. Succeeding makes you feel smart, and the hard levels may call into question players’ intellectual integrity. One player wrote, “if you think you’re smart, buy this game, and realize that you are not smart enough.”

Learning Science

Spatial Contiguity

When you hover over a command in your inventory, a tooltip appears nearby to tell you more about what that command does.

Similarly, when you right-click a command that is in your circuit, a menu pops up that allows you to make adjustments to that command like switching its color, or switching an add-bond command to a remove-bond command.

These tw0 mechanics leverage spatial contiguity by keeping the explanations/elaborations of a command physically nearby the command, itself (as opposed to say having one centralized text box on one side of the screen where all tooltips are displayed). This reduces the cognitive load required to make the connection between the command and the additional information provided by the tooltip or menu. That said, the right-click menu that pops up actually covers the command you clicked on, rather than being next to it. This may make it a bit harder to remember exactly which command you clicked on. In the example in the above picture, even though I can choose whether to set the selected command to a bond+ or bond-, I can’t tell just by looking at the popup menu whether the command I selected was already bond+ or bond-, so I have to remember which it currently is in order to know if I should make a change. This could be easily fixed either by highlighting the current selection in the popup menu, or simply moving the placement of the popup menu to avoid obscuring the selected command in the circuit.

Feedback

The game gives some correctness feedback, but very little corrective feedback. When two atoms collide, the simulation crashes and the player is told to stop that from happening, but they are given no direction as to how to do so. The feedback is immediate when the problem occurs, and gives some indication of what the type of problem is, if not how to solve it. Creative and/or persistent players can conjecture what should fix the problem, implement their idea, and then analyze the result to see what if anything should be changed about the new solution, but there is very little help that will be given to players who are truly stuck.

This is unfortunate, because it increases the level of grit required for players to persist through the more challenging levels, which will precisely deter the players who could most benefit from increasing their frustration tolerance. That said, it’s not obvious what kinds of feedback could be useful without simply giving away the complete solution. One method could be to develop a series of incomplete solutions that get closer and closer to fully solving the problem. Stuck players could ask for hints and receive scaffolding that gets them started. They could ask for more and more hints until they are finally shown the complete solution if they truly can’t get it. The hope here is that by revealing partial solutions, players might notice elements of deep structure that solves some of the issues their implementations face. That might inspire players to try new things before asking for another hint.

Two problems with this strategy are how to address the possibility that players abuse hints and learn very little from them, and how to allow players to feel they are expressing themselves when there is only one sequence of solution hints, which might differ significantly from their approach. Even if a player was on a possibly right track, the hints might steer them away from their approach in a way that detracts from the players’ sense of ownership over their solution.

A simple strategy for dealing with the first problem (hint spamming) could be to require that players try a number of new solutions before requesting another hint. This wouldn’t make it impossible to abuse the system, but it could encourage players to try something new before blasting straight to requesting a functioning answer.

The second challenge is more difficult to address. One route could be to instead develop a number of different solutions to each level (each broken down into a sequence of partial solutions), and to create some measurement of similarity between a player’s current attempt and each solution path, so as to select the hint that best aligns with what the player is currently attempting. This is time consuming and technically challenging, however, so it may not be feasible for a small game like this.

Segmentation

The game does a good job of introducing concepts and techniques in a gradual manner that avoids overloading the player with too many new moving parts at once. This allows the player to master the basics of moving the circuits around where they want, inputting new atoms, picking up and dropping atoms, and such before dealing with the more complex manipulations like rotate and sync. Likewise, the player has many opportunities to grapple with individual reactors before contending with the need to organize multiple reactors into a greater system. These things together lower the cognitive load to make the game more accessible to learners, which keeps it from getting too frustrating too quickly.

Linking

After introducing a concept or technique in isolation, the game does a good job of integrating that into successive levels. Once you learn how to use sync, you will continue to rely on it for the rest of the game. Each new command gets re-used in ever more complex contexts in ways that show their interrelated usefulness. Dropping has a particular relationship with output, for example. You can’t score a completed molecule without dropping it into the correct zone and then calling the output command. Every level requires calling these two commands in the right way, in progressively more difficult problems. Using these together over and over helps to implicitly crystallize them into one larger technique of dropping & outputting a completed molecule. Once these are chunked together conceptually, it’s easier to use them more fluently to efficiently solve harder problems.

Synthesis

In the end, SpaceChem is more about the satisfaction of completing a challenging puzzle than it is about learning. The techniques at your disposal bear certain analogy to computational concepts of loops, parallel processing (and the challenges of asynchronicity), and iterative bug-fixing, but they are too abstracted away from real computational problems to serve as meaningful practice in computational thinking. Likewise, the chemistry knowledge involved is rather shallow compared to the overall complexity of the game, so most players able to succeed are likely to know most of the chemistry content the game includes (some of which is fictional, anyway).

SpaceChem does not teach you how to program, debug code, balance chemical equations, or make the kinds of calculations common in high school chemistry.

That said, SpaceChem does have the potential to introduce players into some of the dimensions of computational thinking that people interested in computer science will need to contend with. Players won’t learn how to wrangle asynchronous function calls, but they may learn that it’s a problem if one part of your program depends on another that takes longer to execute. Likewise, they won’t learn how to debug a program, but they may learn that when they’re trying to fix something that it can be helpful to attempt a solution, check it, analyze what went wrong, and use that understanding to try another solution that hopefully brings them one step closer to solving their problem. As for chemistry knowledge, if a player somehow goes into the game able to handle rigorous problem solving without knowing the basics of how atoms bond together to form molecules, what the names of the most common elements are, or the chemical formulas for very simple molecules like water, then they will walk away learning some domain knowledge too.

The most interesting thing to be cultivated by playing SpaceChem may be patience and grit. Ironincally, it takes serious determination to overcome the game’s challenges, so the players most in need of this benefit are unlikely to reap it. Still, it is very satisfying to figure out your own way to solve any of the game’s challenges, so there is real potential for players with enough grit to buy-in to develop even more grit by practicing in the face of extreme difficulty.